Biology of the Monarch Butterfly

Description |

(Click thumbnail images for larger photos.) |

The monarch is one of Manitoba's largest butterflies,

with a wingspan of up to 100 mm. The body of the butterfly

is black with some white spots. The upper surfaces of the

wings are orange with black veining. The wing margins are

black with white spots. Males can be distinguished from the females by a black patch on their hind wings, called a stigmata. Underneath, the

wings are a paler orange, almost beige, with the same black

veining and borders. The caterpillar (larva) of monarchs is boldly patterned, too, with black,

white and yellow banding.

The monarch is one of Manitoba's largest butterflies,

with a wingspan of up to 100 mm. The body of the butterfly

is black with some white spots. The upper surfaces of the

wings are orange with black veining. The wing margins are

black with white spots. Males can be distinguished from the females by a black patch on their hind wings, called a stigmata. Underneath, the

wings are a paler orange, almost beige, with the same black

veining and borders. The caterpillar (larva) of monarchs is boldly patterned, too, with black,

white and yellow banding.

Report Monarch Sightings directly at: Journey North |

Name

The monarch butterfly is an insect (Class: Insecta), belonging to the subgroup of insects that includes the butterflies, moths and skippers (Order: Lepidoptera; from the Greek, "Lepis" = scale, "pteron" = wing). It is a member of the family, Nymphalidae and belongs to a further subgroup called the milkweed butterflies (Subfamily: Danainae). The monarch is the only species of this group, that contains 300 species world-wide, to occur in Canada.

| Check out these projects: | |

|

|

The common name of this butterfly was assigned by early settlers to North America. There was, at the time, a King William (the 3rd, apparently), Prince of Orange, state holder of Holland, who would later be named King of England. The butterfly's colour lead to the name: monarch.

Its scientific name, Danaus plexippus, is derived as follows. (Or maybe not. I couldn't track down a definitive statement anywhere, so this is an educated guess.)

Genus: Danaus (Latin) from "Daunus", a fabled king of Apulia.

Danaus had 50 daughters who he ordered to kill their husbands on their wedding night. Each was given a dagger to carry out the deed. All but one complied. Perhaps this has to do with the stigmata mark on the hind wings of male monarchs?

Or perhaps it derives from "Danae". In Greek mythology, she is the woman who was imprisoned by her father because it was foretold that her son (Perseus) will kill him. Zeus comes down to the chamber as a golden shower and sleeps with her. They have a baby. Her father seals her and the baby in a chest and sets it a drift.

Species: plexippus (Greek) from "Plexippos", one of the numerous sons of Aegyptus.

Aegyptus's 50 sons married Danaus's 50 daughters. Plexippos is one of the sons killed by Danaus' daughters. Sounds like the stab-mark theory relating to the stigmata on male monarchs may be the key?

As I've mentioned before, scientific nomenclature stemming from earlier, more "romantic" times can be a little strange. At least the scientific name has some relation to the species' common name, in keeping with the theme of royalty. It just doesn't have much to do with the biology of the critter. I might have suggested "Asclepiovorus migratoria-rex". Read on and you'll be able to figure out why.

Monarch Relatives

Here's some of the monarch's relatives in the Subfamily Danainae. They are a common group of tropical butterflies and many even show seasonal migrations like our monarch, though none come close to migrating over the amazing distances the monarch does.

Here's some of the monarch's relatives in the Subfamily Danainae. They are a common group of tropical butterflies and many even show seasonal migrations like our monarch, though none come close to migrating over the amazing distances the monarch does.

Distribution

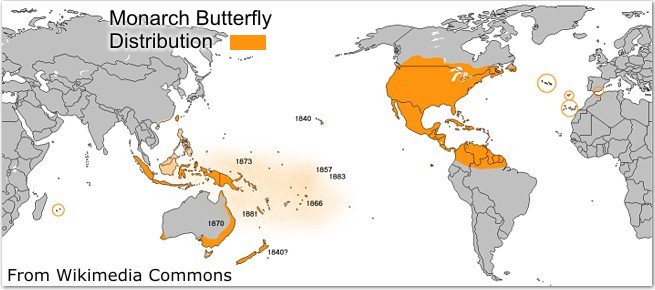

Monarchs occur throughout North America south of the boreal forest zone, in Central America and northern South America. (It has recently been determined that the South American monarch and those found on Jamaica and Hispaniola are separate species, D. erippus and D. cleophile, respectively. Their distributions are not shown on this map.) Monarchs have been introduced to the Hawaiian Islands and to Australia, and are thought to be spreading around to other islands in the Pacific ocean on their own. There are 3 separate populations in continental North America: one east of the Rocky Mountains, another west of the Rockies, and a third, non-migratory population in Florida and Georgia. In Manitoba, they occur in the southwestern 1/3 of the province up to the edge of the boreal forest (see migration map below).

Habitat

Just about anywhere you can find milkweed plants (Genus: Asclepias) and open meadows, you can find monarch butterflies. They frequent prairies, meadows and wetlands, but avoid thick forests. Food for the caterpillars, milkweed plants, and for the adults, flower nectar, are found mainly in grasslands and meadows in Manitoba, so that's where monarchs tend to be.

Their amazing migration seems to be what gets people most excited about monarchs, so we put the migration section here, even before the Life Cycle section (next page). |

Migration

Monarchs are thought to be the only butterfly that truly migrates. Other species emigrate out from certain areas as their food supply emerges with the changing seasons, but in no other species do adults actively return to a certain site at the end of the growing season.

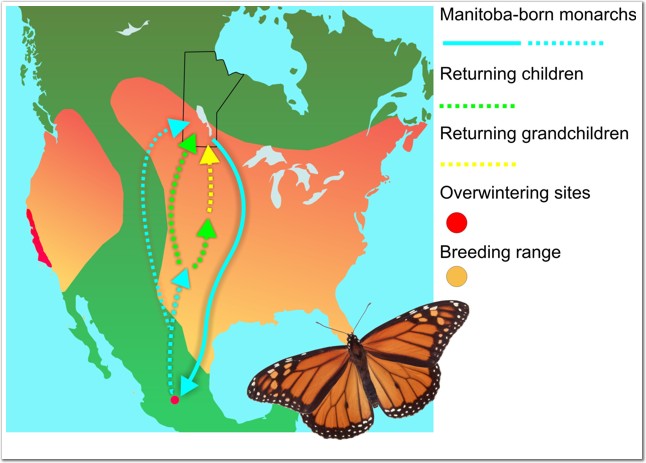

Monarchs must travel to and from Manitoba each year, though it's unlikely that any one butterfly that leaves this province will ever return. Most of those making the return trip will be their progeny. Adult monarchs hatched out here in mid to late summer will fly south all the way to the wintering grounds in central Mexico, over 3000 km away! They reach the wintering grounds by mid-October, averaging over 50 km per day on their southward migration. In spring, around mid-March, our Manitoba monarchs will begin the journey northward, but most only make it as far as the southern US, where they will start a new generation. (Research published in 2011 shows that up to 10% of monarchs returning to Canada have made the entire round trip. The numbers that might make it back to Manitoba are unknown.) The first monarchs to make it back to Manitoba in late May or early June are likely the children of the ones that left here the previous fall. Some of the grandchildren of our original Manitoba monarchs may make it to Manitoba, too, later in the summer. (The monarchs living west of the Rocky Mountains migrate to sites in southern California to overwinter.)

Check out this article: Migratory Connectivity of the Monarch Butterfly. |

Why do monarchs migrate? In spring and summer their

northward journey gives them access to more and more

emerging milkweed plants for their caterpillars and gets the

adults into areas where there is less competition for flower

nectar. But why south to Mexico in the fall? Are they

seeking warmer climes with abundant food? Actually, they are

seeking the opposite. What monarchs need to successfully

overwinter are cool, moist, protected surroundings. They

find these conditions in mountainous regions of  central

Mexico. Monarchs congregate by the millions, in a few

isolated locations in forests within the mountain valleys.

These overwintering sites were not even discovered until

1975! And that was only after a lengthy investigation

involving a tagging program that saw thousands of monarchs

fitted with tiny wing tags!

central

Mexico. Monarchs congregate by the millions, in a few

isolated locations in forests within the mountain valleys.

These overwintering sites were not even discovered until

1975! And that was only after a lengthy investigation

involving a tagging program that saw thousands of monarchs

fitted with tiny wing tags!

In their Mexican retreat, the monarchs have fairly stable weather conditions, with cool, but not freezing temperatures (monarchs are not freeze-tolerant), high humidity and protection from damaging winds. They converge on very small patches of forest and cluster together, often covering the individual trees. They rest and conserve their energy, drawing slowly on their stores of body fat, produced from the nectar of flowers they visited on their journey south. And there they remain, rousing occasionally to flutter about and perhaps sip some water from local ponds, then return to their hibernation, until about mid-March. With the return of spring, they rouse and begin their journey northward.

How do monarchs migrate? It's thought that monarchs use the position of the sun, combined with an innate circadian rhythm, and the earth's magnetic field to determine north and south while on their journey. Monarchs are strong fliers, but also make use of favourable winds, and may even make use of rising columns of air, thermals, to gain altitude, then glide for long distances without expending energy in flapping. In North America, the funnelling effect of the shape of the southern U.S. and central Mexico likely helps monarchs end up in the same places each year.

There is still much to be learned about monarch migration. For example, how do changing environmental conditions in late summer turn off reproduction in the emerging adults and "flip their switches" from "fly north" to "fly south"? The real secrets of why and how monarchs migrate to the exact spots that they do, still remains trapped within their genes.

Food

Food for adult monarch butterflies consists mainly of

flower nectar. They fuel their great travels and

reproductive efforts by sipping this sugary solution from

obliging plants. The plants are, of course, taking advantage

of the monarchs and other insects to do the job of

pollination. Most of their favourites fall within the

Asteraceae family of plants, including such things as

fleabanes (Erigeron spp.),

asters (Aster spp.), sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) and blazingstars (Liatris spp.), but they are

not really that selective when it comes to flower nectar.

Any flower that has available nectar could be visited by a

monarch. (For more information on nectar sources for

butterflies in general, check out our Butterfly

Gardening article.)

Food for adult monarch butterflies consists mainly of

flower nectar. They fuel their great travels and

reproductive efforts by sipping this sugary solution from

obliging plants. The plants are, of course, taking advantage

of the monarchs and other insects to do the job of

pollination. Most of their favourites fall within the

Asteraceae family of plants, including such things as

fleabanes (Erigeron spp.),

asters (Aster spp.), sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) and blazingstars (Liatris spp.), but they are

not really that selective when it comes to flower nectar.

Any flower that has available nectar could be visited by a

monarch. (For more information on nectar sources for

butterflies in general, check out our Butterfly

Gardening article.)

The most important food for monarchs is that which the caterpillars eat, milkweed (see If You Grow It, They Will Come, next page). Monarch caterpillars, like the caterpillars of most butterflies and moths, have evolved fairly restricted diets. Monarch caterpillars eat the flowers and leaves, and sometimes the seed pods, of milkweed plants. They are one of the few caterpillars that does eat members of the milkweed family. These plants contain a thick, foul-tasting milky liquid, hence the name, that flows into areas of the plant that have been damaged: eaten or broken. This liquid is primarily intended as a deterrent to insects eating the plant. Monarchs can get partly around this defence, by chewing holes in the base of the main veins of leaves before they eat them, thus preventing excess "milk" from pouring into the leaf. The plants have other chemical defences, though, one of which the monarchs even turn to their own use. (See the video "Egg to Monarch Butterfly" on the next page.)

Toxic Defence and Mimicry

Milkweed tissues contain compounds, called cardenolides, that are quite toxic. Intended by the plant as a chemical deterrent to being eaten, monarch caterpillars are immune to these and actually accumulate the toxins in their own tissues, rendering them toxic, too. The bold patterning of monarch caterpillars advertises this fact. Should a bird attempt to eat a monarch caterpillar, it will become ill, usually vomiting out the caterpillar, and will refrain from eating any more. Bold warning coloration, reinforced by the occasional bad meal, leaves monarch caterpillars safe from most avian predators. If attacked, a monarch caterpillar will roll up in a ball and fall off the milkweed plant to the ground below, where it will remain curled up until the danger has passed. In this position its bright warning colours are even more pronounced.

No defence is perfect, however, and just as the monarch

caterpillars have evolved resistance to the milkweed's

toxins, so too have other insects developed resistance to

the caterpillar's defence. Several kinds of parasitic flies

and wasps, plus a variety of micro-organisms take their toll

on monarch caterpillars.

No defence is perfect, however, and just as the monarch

caterpillars have evolved resistance to the milkweed's

toxins, so too have other insects developed resistance to

the caterpillar's defence. Several kinds of parasitic flies

and wasps, plus a variety of micro-organisms take their toll

on monarch caterpillars.

Monarch butterflies retain the toxic defence that originated in their caterpillar stage. Their bold black and orange coloration advertises this, and potential predators learn to avoid this species. This defence is so good that it even offers protection to another unrelated species of butterfly, the viceroy (Limenitis archippus). Viceroy butterflies, which are also quite common in Manitoba, are not toxic or bad tasting, but they have evolved to look very similar to monarchs, thus gaining some protection from predators that have learned not to eat monarchs. This sneaky trick is an example of "Batesian mimicry", a fairly common technique employed in the insect world.

Carry on for Even more about Monarchs!

![]()

Return to Manitoba Monarchs | Summer Issue | NatureNorth Front Page